History of Projection and Sound at the Electric Palace

The Electric Palace is a rare surviving example of an intact and unchanged Picture Palace from the Edwardian period. At one time, there would have been hundreds of little suburban cinemas like this dotted around the UK.

Our cinema does have a particularly unique feature which you don’t see elsewhere, though. On the side of the building, adjacent to the front pediment, you can see a winch. Below this there is a strong ladder, attached to the wall.

In the early period of the cinema’s operation, films in their cases would have had to be hauled up the ladder. Film was very flammable and had to be kept away from the audience while it was being projected. The only way for anyone to gain access the ‘lamp room’, which is where the projectors are housed, is via this route.

The winch was put in place in 1986, following the cinema’s refurbishment, to make moving film cannisters and equipment easier. The introduction of safer film stock in the 1950s reduced the risk of fire, yet our projectionists have always had to ascend and descend via the metal ladder, and they still do today.

A gas-powered Picture Palace?

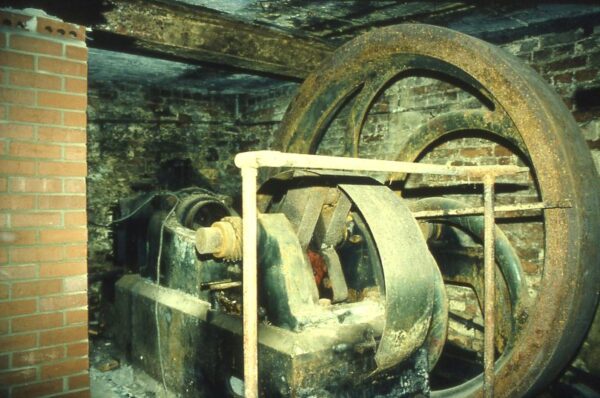

The Electric Palace in Harwich opened in November 1911. At that time there was no electricity supply in the town, so the Electric Palace had to make its own. Situated in the basement there was a Crossley gas engine, which ran off the town’s gas supply. This powered a generator which produced electricity for the cinema.

The lighting inside the auditorium would have been provided by gas lamps and it’s thought that there were electric bulbs at the front of the cinema, in lines above the pay box.

Early Projectors

Early projectors used arc lights to illuminate the film as it passed through the ‘gate’. Arc lights were extremely bright, the brightest light source available at the time. They consisted of positive and negative carbon rods which, when ignited, formed an ‘arc’ of flame between the two ends.

The Electric Palace had two projectors when it first opened, possibly a Kalee and certainly a Gaumont Chrono machine, which were popular projectors at the time. They produced a good, steady bright picture on the screen. The screen onto which the picture was projected was simply a white painted area on the back wall of the cinema.

It is possible that the first projectors used at the Electric Palace had previously been used in Charles Thurston’s travelling Bioscope shows before they were installed here. The first projectionist at the Electric Palace was John Barker. From the age of 16 he had been working on travelling picture shows and he had been the operator on Charles Thurston’s very famous ‘Royal Picture Show’ just prior to the opening of the Electric Palace.

As time went on, the projectors were updated with different models. In around 1924, the Electric Palace was taken over by a Mr Bertram. He is said to have brought in new people, including a Mr Podd, who was the engineer responsible for both the power generating plant and the projectors. According to him, the original Gaumont machine was replaced by another Gaumont that Mr Bertram brought with him from another cinema he owned.

Films also got longer. At first when each reel of film came to the end, a title came up saying ‘End of Part 1’ or ‘End of Part 2’. If the cinema only had one projector, the audience had to wait until the next reel was threaded up.

The Changeover

Once mains electricity became available in Harwich, the Palace would most likely have adopted the practice of using two projectors with changeovers to allow feature-length films to be screened without breaks. Films no longer had the ‘End of Part’ text coming up on the screen for all the audience to see. The projectionist needed to be familiar with the last few shots of a reel so that the next projector could be started up and the outgoing one stopped. Reel one would be fed through the projector, containing what was currently playing on the screen, while reel two would be in the second projector, ready to start.

Outgoing reels had to be rewound, ready for the next showing. The Electric Palace had a small rewind room next to the projection box for this. The carbon light sources in one machine would be refreshed while the other machine was running.

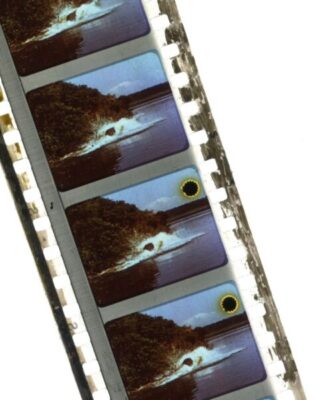

In 1930 ‘cue dots’ were introduced. Towards the end of the first reel, the projectionist would watch the film on the screen through one of the portholes for ‘the eye in the sky’ – a blinking dot in the top corner of the picture. This first cue would tell the projectionist to turn on projector number two.

When sound films came in, changes from one reel to the next had to be very precise and the films now had to run at a constant speed which was 24 frames per second, equal to 90 feet per minute.

Sound comes to the Palace

The first ‘talkie’ shown at the Palace was The Singing Fool staring Al Jolson. It was first screened here on 10th March 1930.

By this time only about a third of all UK cinemas were wired for sound, which makes the Palace a surprisingly early adopter of sound for the small regional cinema that it was and is.

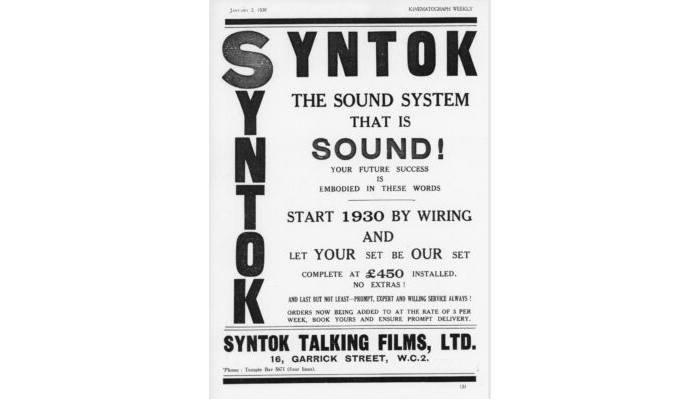

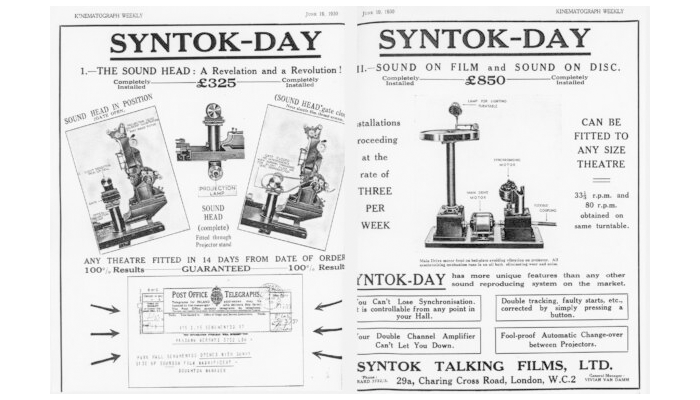

The original 1930 sound installation at the Palace was a sound-on-disc system made by “Syntok Talking Films Ltd.”

A man called Sid Mills worked at the Palace as a creator of sound-effects when the silent films were playing. However once the sound equipment was installed his new job was to change the records.

By all accounts the Syntok equipment was less than satisfactory. It was unreliable, the projectionists found it difficult to use and it also seems that the poor-quality of the sound acted as a deterrent to audiences who preferred to go elsewhere.

The Syntok sound-on-disc system was replaced in 1932 by a Western Electric sound-on-film sound system. Two large Western Electric 12A full-range horn loudspeakers were hung from a substantial wooden structure which was placed behind the screen. This would have meant an end to the variety acts that used the stage.

The Bostok circuit

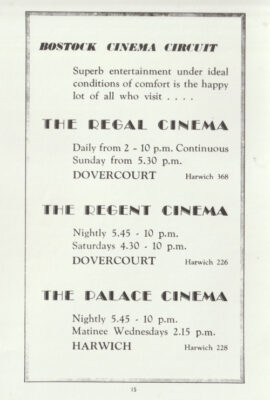

In 1932 the cinema changed hands for the third time, this time to the Bostok circuit which also owned the Regent and Empire cinemas in Dovercourt. No significant changes seem to have been made to either sound or projection equipment before the closure of the cinema in 1956.

Although CinemaScope launched in 1953, CinemaScope films were not screened at the Electric Palace as the sound equipment was too outdated to play them. The cinema was badly affected by the flood in Harwich in 1953 and it closed soon afterwards. It was not until re-opening in 1981, following a major refurbishment project, that CinemaScope films could be shown at the Electric Palace for the first time.

Restoration in the 1970s

The projectors in the photo included in this slideshow are Kalee Dragons, fitted with Kalee Vulcan lamp houses. Carbon arcs were still used as light source. The projectors and lamps were replaced in 1983 by Kalee 20s with Peerless arc lamps. Also in 1983 the mono valve amplifier was replaced by a basic stereo sound system.

In 2000 a grant from the Arts Council allowed the Electric palace to purchase a new Dolby Digital Stereo Surround Sound system, with a Dolby CP500 audio processor. The Peerless carbon arc lamps were replaced with new Xenon arcs at this time too.

A Xenon bulb is filled with xenon gas and has a metal electrode at each end of the lamp. It creates light by applying a high-voltage to the xenon gas at high pressures. One advantage of these electric lights was that longer films could now be shown without any interruptions.

In 2011, digital projection equipment was installed giving improved picture and sound. This was a Christie CP2220 digital projector and a Doremi DCP-2k4 server. A Dolby CP750 audio processor was added to the sound system to handle the digital cinema audio.

The two Kalee 20s with Peerless lamps are still there, right next to the digital projector, meaning that the Electric Palace can still show ‘film’ in its earlier form.